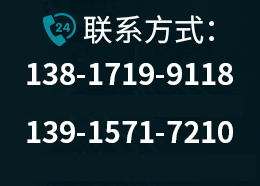

�N�۟ᾀ:

138-1719-9118

�P���҂�

ABOUT US

�K�����v���C�Ƽ�����˾

��Ʒ�|

�̓r��

��ȫʡ��

�K�����v���C�Ƽ�����˾���ڻ�е�豸�ӹ�������ҵ����רҵ������Ʒ�֡���������������ң���Ҫ�bƷ��Y3150/3�L�X�C��Y3150���S�����͡�YK3150���S�����͡�Y3150CNC4���S�����͡�YBS3120�����͡�YK3120���S�����͡�Y3120CNC3���S�����͡�Y3120CNC5���S�����ͣ������N���M�ͺͷǘ˸��b�͝L�X�C��

|

|

������

NEWS CENTER

|

|